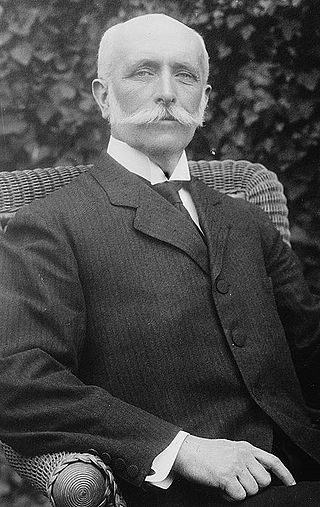

This week we are going to take a look at the political program of Porfirio Díaz. He was President of Mexico from 1876-1880, then again from 1884-1911, after a 4 year lapse with intervening President Manuel González. Díaz was a military man from Oaxaca, a rising liberal star under President Benito Juárez during La Reforma. In 1876, with the backing of the army, he issued the Plan de Tuxtepec, a revolt against the then-current regime and declaration of himself as President of Mexico. After he took office, he amended the Constitution of 1857 to proclaim no re-election and a presidential term of 4 years.

The Mexico that Díaz inherited was in shambles. The national debt was out of control, it lacked basic infrastructure such as a consistent railway system, technology and modernization were light years behind other industrializing countries such as the U.S. and Britain, and there was a public health crisis especially in Central Mexico where recurrent floods led to stagnating waters and disease. The reputation of the country abroad was that of a backward nation.

Díaz adopted the slogan “Order and Progress”: in order for Mexico to progress as a nation, the rule of law needed to come first. Díaz effectively squashed opposition, using his army to violently put down agrarian strikes and to execute dissenters. Meyer, et al. write that “rebel leaders who were not shot down on the field of battle were disposed of shortly after their capture… characteristic of Díaz’s attitude toward those who would disrupt the national peace was his reaction to a revolt in Veracruz during his first year in office… ‘Mátalos en caliente’ (Kill them on the spot).” (379) Díaz also established order through the appointment of loyal political cronies into lesser offices such as governors, jefes políticos (district heads), and army officers. In return for their loyalty, these agents were able to enrich themselves and exercise full control over their respective territories, often with a heavy hand.

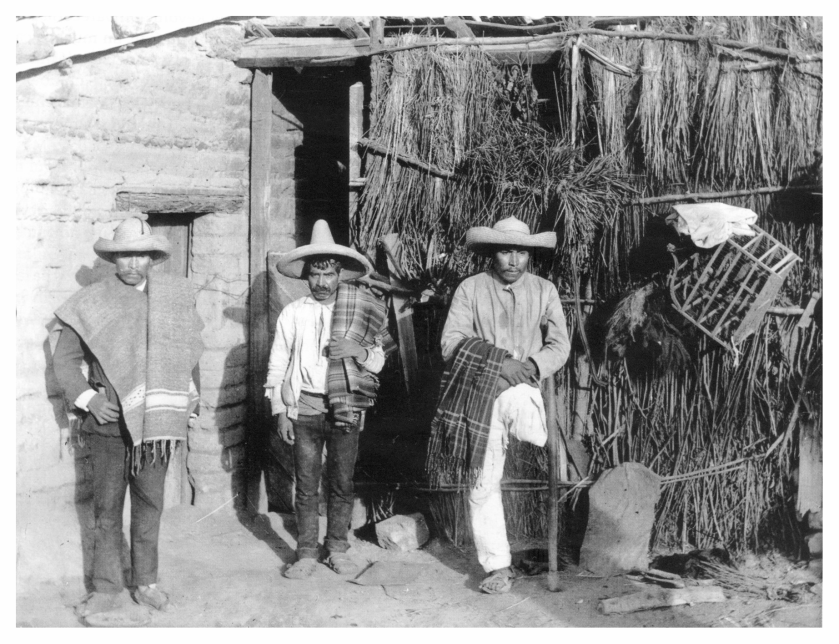

The Porfiriato was also the age of the land-grab. Laws such as the Ley de Deslindes (1883) and the Ley de Terrenos Baldíos (1894) opened the door to large real estate companies and wealthy individuals seizing large tracts of land, land that was often held communally by indigenous communities (ejidos). “If the victims offered armed resistance, Díaz sent troops against them and sold the vanquished rebels like slaves to labor on henequen plantations in Yucatán or sugar plantations in Cuba.” Keen & Haynes, 2013 (257-258). By 1910, it is estimated that 90% of indigenous villages in Central Mexico had lost their communal lands, and that landless peons and their families comprised 9.5 million of a rural population of 12 million. (Ibid) Indeed, this presents a large, systematic problem that eventually became the basis for revolt during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920).

In order to better understand the policies initiated by Porfirio Díaz and his advisors, it is necessary to discuss the ideologies of the era. The first is positivism, the idea famously put forth by Auguste Comte that knowledge is based on natural phenomena, or what can be seen, heard, and touched; therefore, empirical data was prized over metaphysics and theology. Reason and logic ruled the day, and scientific thinking could be applied to social issues in order to find practical solutions. Herbert Spencer’s Social Darwinism was also a component of Porfirian politics. In this school of thought, humans were in a struggle for “survival of the fittest,” where the weak (i.e. the poor, the dark-skinned) would ultimately be overruled by the strong (the rich, the white). The weak were expected to be in a constant state of development to reach the pinnacle of “civilization,” meaning to be assimilated into the dominant culture of the powerful. This theory was the basis for many racially-based policies in the 19th-century, such as forced Indian education and the breakup of ejidos, where unused land was considered to be misused by the natives who were hindering national progress.

In that vein, Porfirio Díaz hired científicos, a group of technocrats who used positivist thinking to “scientifically” modernize society. Most famous of these were José Limantour (Secretary of Treasury) and Justo Sierra (Secretary of Education), who were adherents to the idea of the “inherent inferiority of the native and mestizo population and the consequent necessity for relying on the white elite and on foreigners and their capital to lead Mexico out of its backwardness” Keen & Haynes, 2013 (256). Development was important to the científicos, who strove to make Mexico a desirable place for foreign investment. Limantour was able to make some economic gains for the country. For example, he reformed tariffs, switched the country from a silver to a gold standard, and made administrative changes intended to reduce governmental corruption and graft.

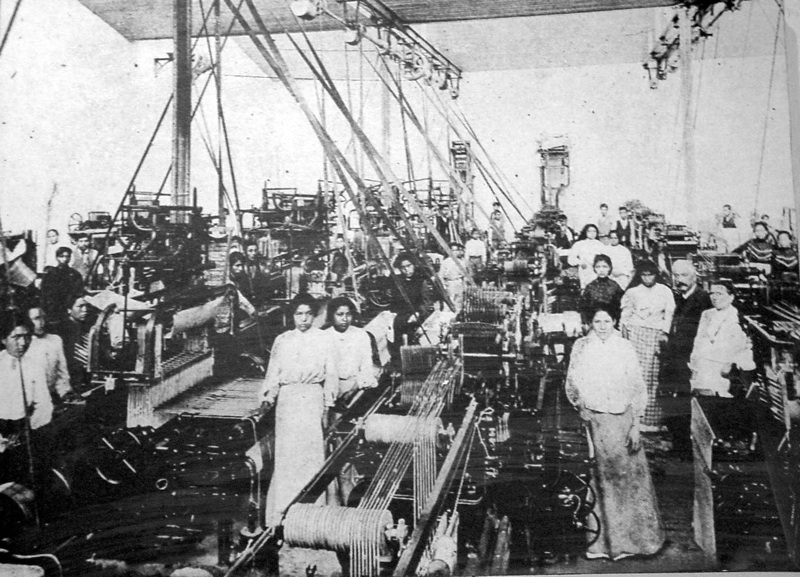

The country began to modernize under this regime, replacing animal and human labor with steam, water, and electric power. Hydraulic and hydro-electric stations were built and machinery came with it. The telephone arrived in the 1880s, and a nationwide telegraph system was finally installed. Díaz hired an overseas engineering firm to oversee the sanitation crisis in Mexico City, and they were able to build a canal and a tunnel to address the flooding problem. A large number of neoclassical public buildings and monuments began to pop up in the cities. Railroads became big business and linked cities together, which expanded domestic markets and furthered economic growth . Foreign investment became important in the areas of mining and oil production, as U.S. and British companies vied for stakes in the industries. Meyer, et al. 2007 (382-389) All of this began to showcase Mexico internationally as a country that was on the rise.

Unfortunately, the material wealth and abundance never trickled down to the people. All of this positive growth masked a dark side. As mentioned in a previous post, the mass expropriation of village lands led to an underclass of peones, agricultural and mine workers who were tied to their lands, paid meager wages, and could never escape a cycle of debt to their overlords. Because of this, trade unions began to grow in the early 1900s. Though often brutally repressed by the Díaz regime, popular unrest began to foment throughout the country, spearheaded by intellectuals such as Ricardo Flores Magón and even wealthy capitalists such as Francisco I. Madero. Critics argued that more aggressive economic and social reforms were necessary to avoid a revolution by the masses.

Features of the Porfiriato such as sham elections and vast patronage networks, administration of justice through force, press censorship and intimidation, and repression of any opposition, ultimately contributed to its downfall. In conjunction with a recession that hit Mexico hard in 1906-1907 and crop failures from 1907-1910, the Mexican people were largely unsatisfied with the regime. The opposition gradually began to organize and eventually forced the resignation of Porfirio Díaz on May 25, 1911.

We’ll discuss the events leading up to that in the coming days, as next time I explore in more depth the end of the Porfiriato and the beginning of the Mexican Revolution. I hope that this post has been useful and has provided a good overview of a complicated era (Mexican history is filled with complicated eras!). As always, please like and share the post, and comment down below if you’d like to join the discussion. Until next time!